Many children draw trees in a stereotypical way—a cloud like form placed over two vertical lines. When I see children of Class 7 drawing trees like the children of Class 3, 4, 5 or 6 would, it reveals a problem. If a tree has to feature in their writing, we would definitely be able to distinguish a 3rd grader from a 7th grader in the way the word is used in a sentence, or how it carries specific descriptions. Furthermore their knowledge about plants and trees is deep. Many of them have grown up in farming cultures and know their plants intimately. They are store-houses of knowledge nurtured by their everyday experience and observations.

In Class 5, a boy mechanically drew some trees next to a house and showed it to me. When I asked him what trees they were, he pointed to one and said that it was a neem tree. I asked him if he could try and draw some of the characteristics of the neem tree. He said he didn’t know how to. I asked him if he could differentiate a neem from a mango tree if he saw the two on a road. He said he could, because their leaves differed. His tree had no leaves. He looked at his drawing and then told me “But this is how a tree is drawn”.

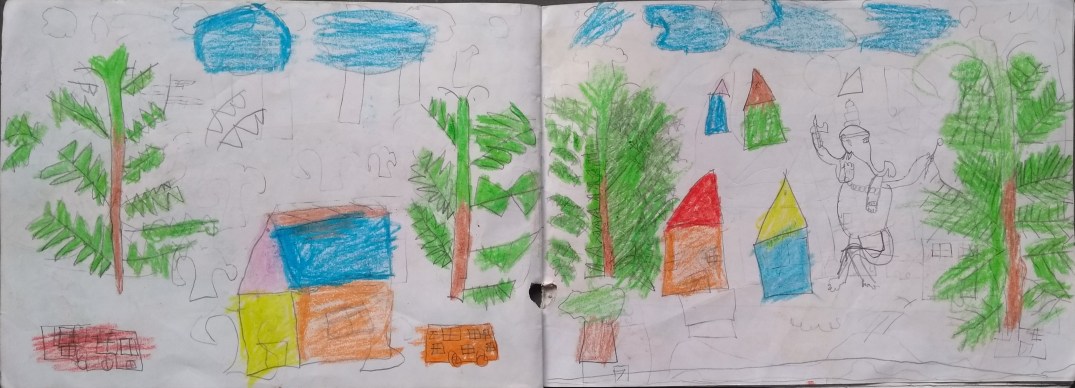

I fetched my laptop and opened a folder containing Gond paintings. I showed him many images that depicted trees, each one drawn with unique characteristics, some of them morphing into other forms, some inhabited by birds, some with people climbing on them to fetch mangoes. No two trees were alike. He enjoyed the visuals and so did the others who gathered around us. That day’s session had to end by then. In the next session, the same boy came back with the same cloud tree and told me that that was the only way he could draw a tree. I asked him to recollect the visuals we saw in the previous session. His eyes lit up as he remembered the houses set on a tree and the people collecting mangoes. He then looked at his drawing disappointed and said “I don’t know…”

I asked him if he had seen crops grow in the field. He said yes. I asked him to narrate to me how it all began with a seed. Just as he excitedly began, I suggested that he drew while narrating. He drew a tiny oval seed and as I kept asking “And then what happens?”, his drawing grew along, first as a sapling, then the leaves emerged, the stems grew into branches and more leaves emerged and soon we had a pretty good tree. We then looked at the tree he drew before and the tree he just drew… I asked him which he preferred. He preferred the tree that he grew from a seed.

In Class 7, one child had a scene with trees on the land and clouds in the sky. The clouds were hurriedly drawn with smiling faces. We discussed how clouds looked and how they could be drawn convincingly. When I returned to her drawing after she made some edits, I pointed to her cloud form and asked her what it was and she said “cloud”. When I pointed to the tree she had drawn, she smiled and said “tree” but quickly added that she hadn’t noticed that she drew trees like clouds. Another boy in the class said that trees are commonly drawn like this and so they draw it that way too. I asked the class whether the common picture matched their observation and knowledge. They said it didn’t and one of them said that their individual perspective got lost in the common articulation.

Many of our traditional artists may have been illiterate but their visual languages continue to enrich our lives and educate us about the worlds we share while also giving us an insight into their unique world-views.

Malavika Rajnarayan, 2018